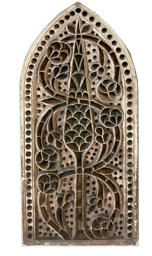

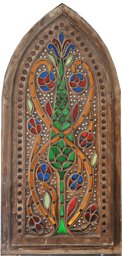

From a technical and iconographic point of view, this stucco and glass window corresponds to one of the standard types of qamariyya widespread in Egypt during the Ottoman period. Similar windows can be found in several of the collections studied (see for instance IG_18, IG_173, IG_355). The representation of a cypress tree surrounded by a flower tendril is a widespread motif in Islamic arts. It can be found in numerous other media, such as ceramics, wood panelling, wall paintings, and textiles, over a long period of time, and in both sacred and profane contexts.

Stucco and glass windows of this type are illustrated in 19th- and early 20th-century publications (see for instance IG_42, IG_47). The cypress-tree motif also aroused the interest of Western artists and architects, as is attested by the significant number of sketches and paintings of the motif (IG_118, IG_136, IG_150, IG_153, IG_438, IG_439, IG_468), as well by the replicas of such windows installed in Arab-style interiors across Europe (IG_56, IG_64, IG_427–IG_430).

The French naval officer and novelist Pierre Loti (1850–1923), who had this stucco and glass window installed in the northern gallery of the so-called mosque built between 1895 and 1897 in his family’s house in Rochefort (France), was familiar with such windows from his extensive travels. In 1894, he embarked on a journey through Egypt, Palestine, and Turkey and subsequently published his observations and experiences in the trilogy Le désert (1894), Jérusalem (1895), and La Galilée (1896), as well as in the novel La mosquée verte (1896). In Jérusalem (Loti, 1895, p. 72), Loti relates his visit to the Dome of the Rock and pays particular attention to the stucco and glass windows and their luminous effects. He compares them to precious stones, praises the effect of the stucco grille, and describes the angling of the perforations. According to his accounts, Loti also visited traditional residences. He was even received in two reception halls (qāʾa) in Damascus, which are described in La Galilée and later inspired him in relation to his ‘mosque’ at Rochefort (Loti, 1896, p. 144, 146). In La mosquée verte, he comments on these windows again, this time those in the tomb of Mehmed I in Bursa. After mentioning other furnishings, such as the ceramic tiles and the carpets, the stucco and glass windows are described as follows: “Des petits vitraux, haut perchés, tout près du dôme, et travaillés autant que des pièces de bijouterie, laissant descendre une lumière changeante, comme filtrée au travers de pierres précieuses.” (Loti, 1896, p. 233).

According to Thierry Liot, this stucco and glass window may have belonged to the late 18th-century Damascene house from which the ceiling, mihrab, and woodwork of Loti’s ‘mosque’ at Rochefort are thought to have originated (Liot, 1999, p. 130; see also Giraud-Heraud, 1996, pp. 64–65). While it seems very likely that this window was manufactured in an Islamic land, its design, composition, and manufacturing technique point to Egypt rather than to Syria, which is why it is also possible that Loti acquired the window on the art market. Owing to the window’s formal and compositional characteristics, as well as the state of preservation of the stucco grille and the type of glass used, a dating to the 19th century may be more probable.

The present window seems to have inspired the four replicas IG_427–IG_430, installed next to this one in the qibla-like eastern wall of Loti’s ‘mosque’. Like the replicas, this specimen was protected from the weather on the outward-facing rear side by means of a 4mm-thick pane of glass at an unknown date, but most probably in connection with the window’s installation at Rochefort.