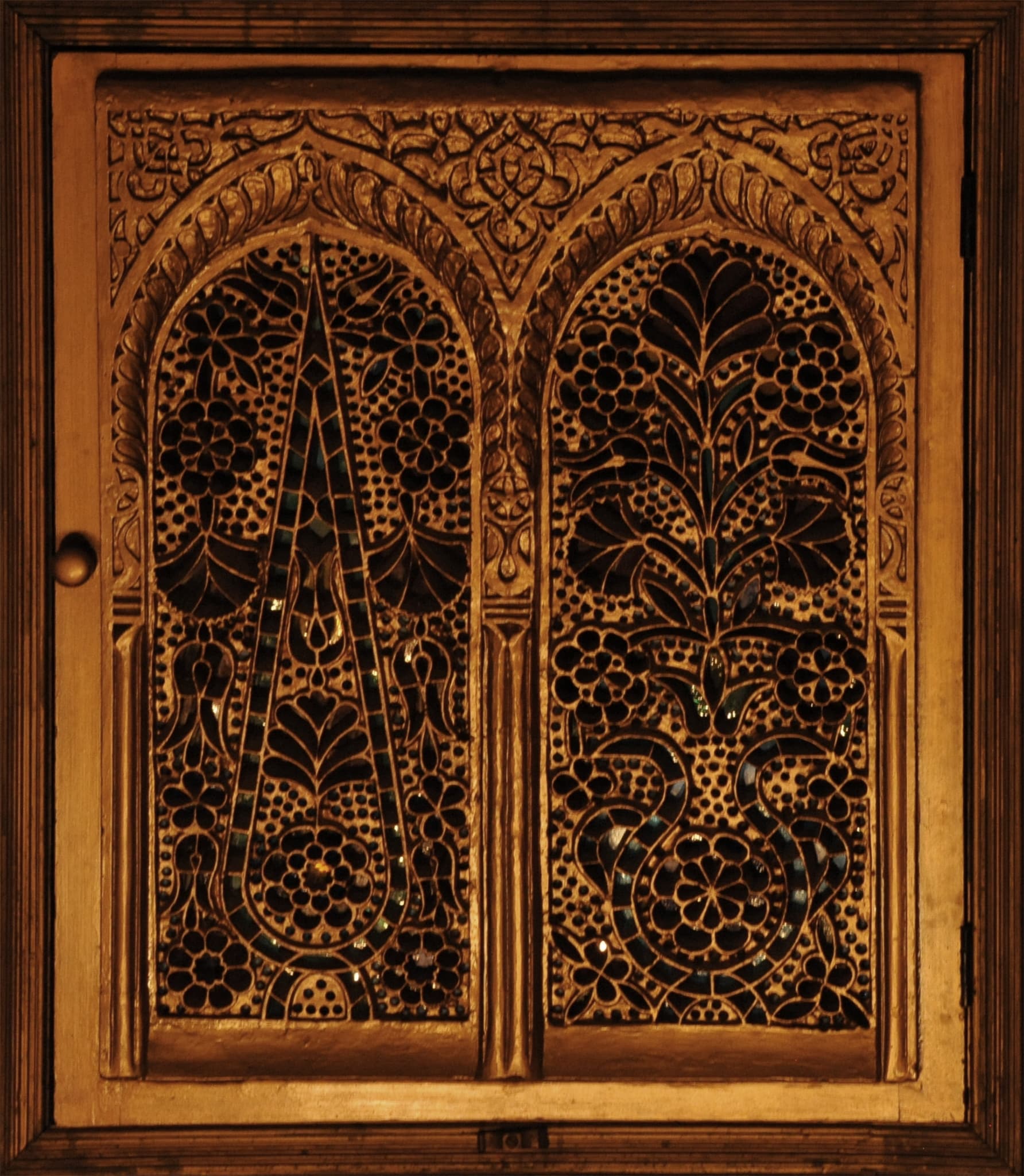

This replica of a stucco and glass window represents an unconventional combination of two regional standard types: while the framing double arch is typical of stucco and glass windows from Tunisia (see for instance IG_270), the representations in the window openings are free translations of Egyptian qamarīyāt. The hand of a Western designer is clearly recognizable. The cypress tree in the left-hand opening and the vase in the right-hand opening have been depicted in a highly abstract manner.

From an iconographic point of view, this replica juxtaposes two of the most popular motifs of Islamic stucco and glass windows during the Ottoman period: the cypress tree and flowers in a vase. Both motifs are widespread in Islamic decorative arts and can be found in numerous other media, such as ceramics, wood panelling, wall paintings, and textiles, over a long period of time, and in both sacred and profane contexts.

Stucco and glass windows with cypress trees and flowers in a vase can be found in several of the collections studied (see for instance IG_18, IG_173, IG_355 (cypress tree) and IG_7, IG_166, IG_176, IG_255, IG_261, IG_356 (flowers in a vase)). They also aroused the interest of Western artists and architects, as is attested by a significant number of book illustrations, sketches, and paintings (see for instance IG_42, IG_47, IG_136, IG_150, IG_153, IG_438, IG_439, IG_468 (cypress tree) and IG_43, IG_149, IG_153, IG_437, IG_443, IG_461 (flowers in a vase)). As of the 1850s, replicas of stucco and glass windows with the two motifs were installed in Arab-style interiors across Europe (IG_64, IG_427–430 (cypress tree) and IG_64, IG_431, IG_484–487 (flowers in a vase)).

One of these interiors is the Arab Hall of the studio-house of the British artist and collector Frederic Leighton (1830–1896) at Holland Park Road in Kensington (London), where the replica discussed here is located. Leighton House was constructed between 1865 and 1895 in five phases after plans by one of Leighton’s close friends, the British architect George Aitchison (1825–1910). Work on the Arab Hall extension began in 1877 and continued until 1881. At the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), various drawings by Aitchison of the Arab Hall are conserved (IG_50–IG_53). Two presentation drawings (IG_52, IG_53) showing the elevation of the east and west walls of the Arab Hall were exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1880. According to an anonymous report on Leighton House and the Arab Hall, published on 1 October 1880 in The Building News, the exhibited drawings by Aitchison showed ‘the decorations as completed’ (Anon., 1880, p. 384). We may therefore assume that the windows had already been installed in the Arab Hall in 1880.

Leighton House is one of the most famous 19th-century artist’s homes, combining living, working, and exhibition spaces, designed according to Leighton’s needs and aesthetic visions (Sweetman, 1988, pp. 189–192; Robbins/Suleman, 2005; Robbins, 2011; Anderson, 2011; Droth, 2011; Vanoli, 2012; Roberts, 2018; Gibson, 2020; Robbins, 2023). Leighton’s studio-house reflects the exotic taste of the time (Walkley, 1994, pp. 52–56), which finds close parallels in the now-lost studio of the British painter Frank Dillon (1832–1908). Dillon, who visited Cairo on several occasions in the 1850s – 1870s, recreated a Cairene interior with wall tiles, wooden furnishings, and two stucco and glass windows in his studio in Kensington (Conway, 1882, p. 196; Walkley, 1994, pp. 70), as attested by a wood engraving published in the second volume of Georg Ebers’s Aegypten in Bild und Wort (Ebers, 1880, p. 96, see IG_117).

The Arab Hall extension at Leighton House reflects the patron’s and the architect’s fascination for the East. As many orientalizing interiors, it is an amalgam of various Islamic styles, arranged around the central theme of the 12th-century Zisa Palace in Palermo. While Leighton was familiar with Islamic art and architecture through his travels to Sicily, Algeria, Turkey, Egypt, Syria, Spain, and Morocco, Aitchison was acquainted with Cairo, among other Islamic cities, where he examined traditional houses. He shared his observations during the discussion following the paper on ‘Persian Architecture and Construction’ given by Caspar Purdon Clarke (1846–1911) and Thomas Hayter Lewis (1818–1898) at the Royal Institute of British Architects on 31 January 1881. On this occasion, Aitchison described the iconographic and technical characteristics of Egyptian qamarīyāt and their sparkling light effects and added that ‘many [were] executed for me in London’ (Purdon Clarke & Hayter Lewis, 1881, pp. 173–174) – most probably referring to the Leighton House replicas that were being made at the time. More than 20 years later, in 1904, Aitchison returned to the subject of stucco and glass windows in his essay ‘Coloured Glass’, where he compared Western stained glass with qamarīyāt and mentioned Leighton House with its ‘windows of pierced plaster’ as an example illustrating the Islamic tradition (Aitchison, 1904, p. 57, see IG_91).

The British architect William Burges (1827–1881), who was a long-time friend of Aitchison and Leighton, must have been aware of these replicas when he planned the slightly later windows of the Arab Room at Cardiff Castle in Wales (IG_484–IG_487). However, Burges opted to execute the replicas at Cardiff Castle in glass, lead, and wood, whereas Aitchison stuck more closely to the Islamic prototypes – at least as far as the material was concerned. According to contemporary sources, Leighton acquired various stucco and glass windows during his travels to Cairo (1868) and Damascus (1873) (see for instance Anon., 1880; Wright, 1896; Rhys, 1900). Unfortunately, the Egyptian windows were damaged during shipping (Rhys, 1900, p. 100), something that apparently happened on other occasions (see for instance IG_43). The glass fell off the stucco lattice, and only part of it could be reused in the replica installed in the west wall of the Arab Hall (IG_56). All other windows had to be filled with ‘English imitations’ (Rhys, 1900, p. 100). The Reverend William Wright (1837–1899), who procured qamarīyāt ‘from a mosque in Damascus’ (Wright, 1896, p. 184) for Leighton during the latter’s visit to the city, adds that the Syrian stucco and glass windows ‘have also been supplemented and matched by coloured glass made in London’ (Wright, 1896, p. 184).