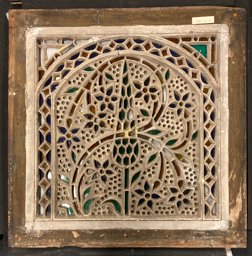

From a technical and iconographic point of view, this stucco and glass window corresponds to one of the standard types of qamariyya widespread in Egypt during the Ottoman period. Similar windows can be found in several of the collections studied (see for instance IG_2, IG_173, IG_355). The representation of a cypress tree surrounded by a flower tendril is a widespread motif in Islamic arts. It can be found in numerous other media, such as ceramics, wood panelling, wall paintings, and textiles, over a long period of time, and in both sacred and profane contexts.

Stucco and glass windows of this type are illustrated in in several 19th- and early 20th-century publications (see for instance IG_42, IG_47). The growing interest of architects and artists in windows with this motif is also reflected in a significant number of drawings and paintings (IG_118, IG_136, IG_150, IG_153, IG_438, IG_439, IG_468), as well as by numerous replicas of such windows installed in Arab-style interiors across Europe (IG_50, IG_59, IG_64, IG_427–430).

The window discussed here forms part of a lot of six qamariyyāt (IG_288–293) acquired by the Glasgow Museums in London in 1896 from the Pre-Raphaelite painter, writer, and collector Henry Wallis (1830–1916). Wallis was an expert in Islamic art and especially ceramics, as several of his publications attest (see for instance Wallis 1885, Wallis 1893, Wallis 1894, Wallis 1899). Due to the lack of documentation, it is not possible to clarify where Wallis acquired the windows. However, several formal and technical similarities suggest that at least four of the six windows were produced in the same workshop and possibly came from the same architectural context: IG_288 and IG_289 as well as IG_290 and IG_293 form a pair, with the same motif and almost identical dimensions. The window here shows the same, but mirror-inverted motif as IG_288. Moreover, both window pairs share the same decoration for the spandrels above the arch. Stylistic features and the manufacturing technique suggest that the windows were made in Egypt.

According to the museum records, the stucco and glass window dates to the 19th century. The structure of the glass and a statement by the Hungarian architect Max Herz (1856–1819) provide clues that indirectly support this dating: the glass shows the characteristics of cylinder-blown sheet glass, commonly known as broad sheet. This technique was uncommon in the Islamic world, but widely used in Europe to produce window glass. European glassworks were among the largest producers of broad sheet in the 19th century. According to Herz, European flat glass was exported to Egypt from the 19th century onwards, as the glass industry there had come to a standstill (Herz, 1902, p. 53).

The poor condition and the weathered surface of the stucco latticework (see Restoration) may be an indication that the window was installed in a building and exposed to the elements. This would mean that it was not produced directly for the art market. It may have been the poor condition of the window that led to the stucco lattice being stabilized by the addition of a coarse fabric on the back (see Restoration).