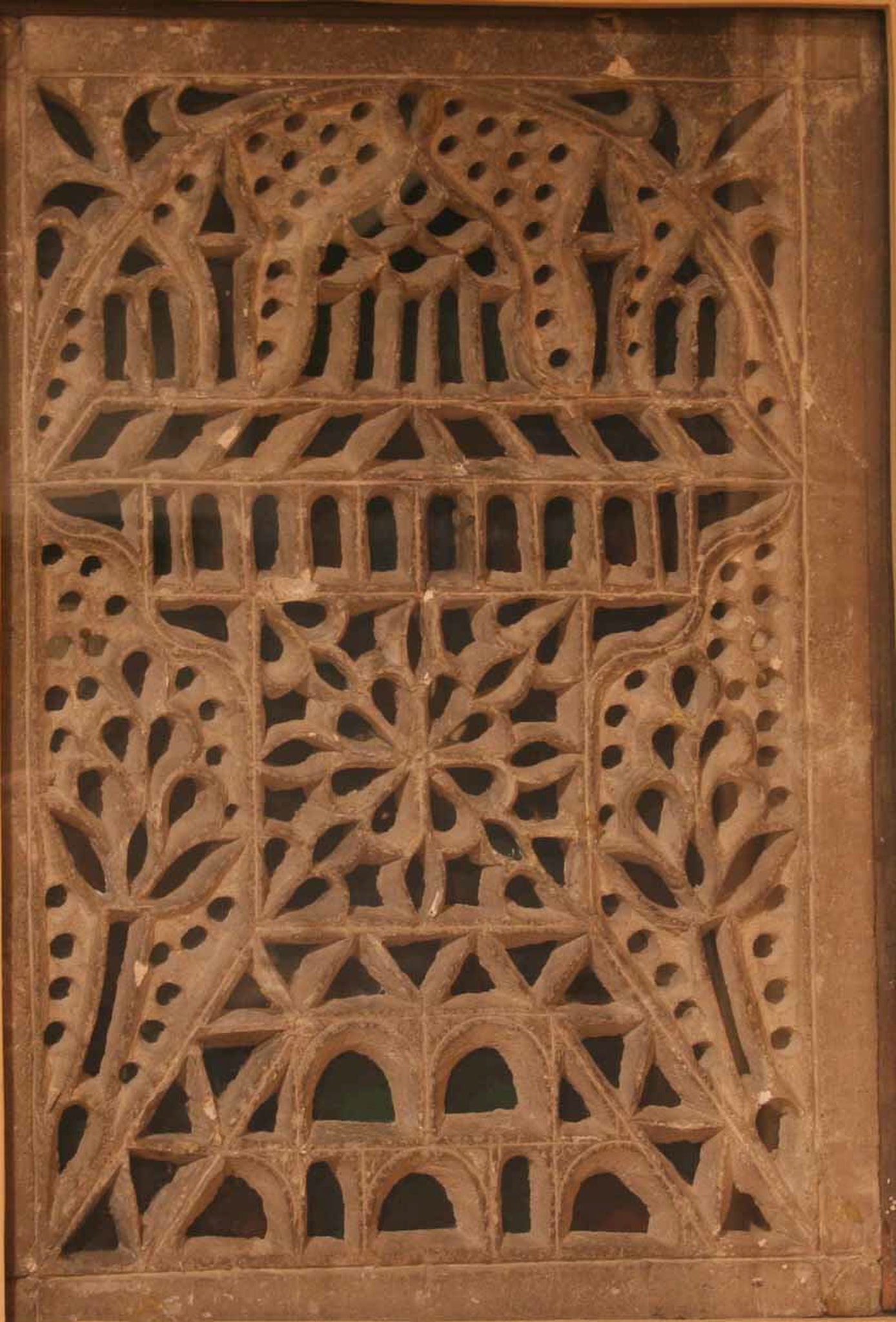

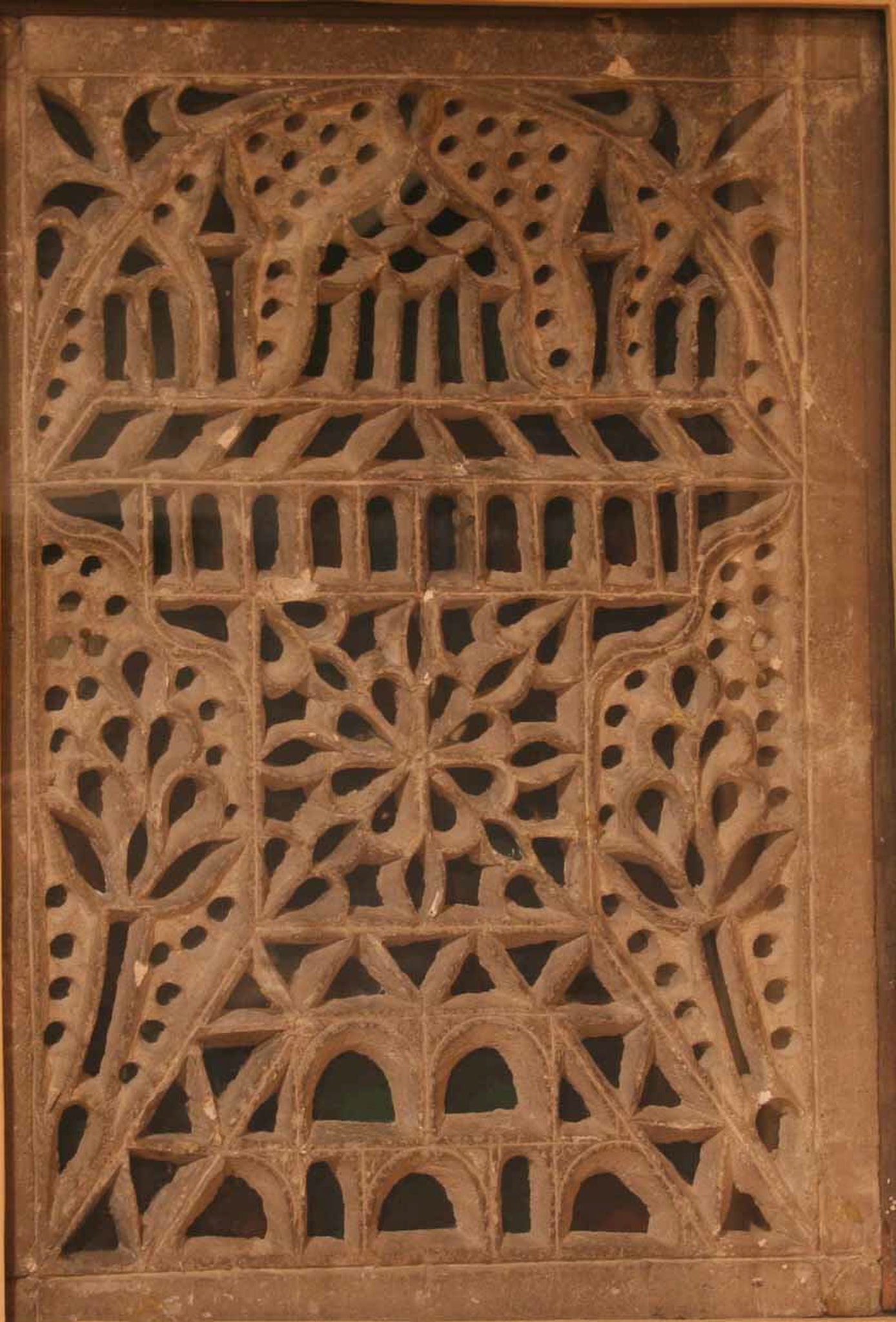

From an iconographic point of view, this stucco and glass window corresponds to one of the standard types of qamariyya widespread in the Middle East during the Ottoman period. A window with the same motif was documented by the British architect James William Wild (1814–1892) during his stay in Cairo in the years 1844–1847, in the mandarah of Beyt Sheikh al-ʿAbbasi al-Mahdi (IG_446).

Representations of mosques and other holy sites can also be found in other media. Most noteworthy are architectural ceramics of the Ottoman period (see for instance Musée du Louvre, OA 3919/556, OA 3919/558, OA 3919/559; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012.337; Victoria and Albert Museum, 427-1900). While in these examples specific shrines such as the Kaʿbah in Mecca are depicted, the mosques shown in stucco and glass windows most likely do not represent any existing mosque. They are often depicted in a schematic way and reduced to their main features, such as the entrance facade, the courtyard, dome(s), and minarets.

In the museum collections studied, representations of a mosque are much less common than other motifs. Other examples of stucco and glass windows with the mosque motif are held at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (IG_184), the Benaki Museum of Islamic Art in Athens (IG_354), and the Museum für Islamische Kunst in Berlin (IG_385, IG_386). Whereas the design of all four windows is very similar, notable differences in the manufacturing technique can be observed: the latticework of the first two windows is carved out of a stucco panel and the pieces of glass were fixed onto the back of the grille by means of a thin layer of plaster; the latticework of the two latter windows is cast, and the pieces of glass were fixed onto the grille during the casting process (Arseven, [c.1952], pp. 207–214; Özakın, 2007, pp. 95–97). These differences point to different regions of origin: the first manufacturing technique is typical for windows produced in Egypt, Greater Syria, and North Africa, while the second technique is common in Turkey. According to our examination of the MET and Benaki windows (see IG_184 and IG_354), these two windows must have been made in Egypt, while the Berlin windows originate from Turkey (see IG_385, IG_386). On the basis of these observations, the window discussed here can be attributed to the first group.

According to the museum records, the window dates to the 18th century. We assume however that the window was made at a later date, possibly around the time it was acquired by Robert Ware (see below). One reason for this hypothesis is the good state of preservation of the stucco lattice, which would have shown clearer signs of weathering if it had been installed and exposed to the elements for a longer period before purchase. Another reason for a later dating is the use of cylinder-blown flat glass (also called broad-sheet). In the Islamic world, sheet glass was usually produced using the crown-glass process, while in Europe, the broad sheet-method was the dominant technique to manufacture flat glass. The Hungarian architect Max Herz (1856–1819) states that sheet glass was imported to Egypt from Europe from the 19th century, because local production had come to a standstill (Herz, 1902, p. 53).

A hand-written letter dated 22 May 1893 to Luigi Palma di Cesnola (1832–1904), the then director of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York provides information on the provenance of the window. The author of this letter, the American architect William Robert Ware (1832–1915), writes that he had acquired this and various other windows in the spring of 1890 from several well-known art and antiquity dealers in Cairo. He mentions [Gaspare] Giuliana, [E. M.] Malluk, [Nicolas?] Tano, and [Panayotis] Kyticas (on their commercial activities see Volait, 2021, pp. 60–64). In his letter, Ware further states that he was told that the windows ‘had been taken from old houses’ and ‘from old mosques, that had been dismantled’, but that he was not able to get ‘any precise information as to their original places’ (Ware, 1893).

In 1893, Ware donated this window as part of a lot of 17 qamariyyāt (IG_169, IG_171–186) to The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Ware, 1893).